The Deriba volcanic crater lake of the Jebel Marra mountain massive.

Jebel Marra, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

An isolated village on Jebel Gurgei in the Jebel Si area of Northern Darfur, where people still lived in a very special type of house with flat-topped roofs, called “Torrontoga”. In the Fur language “tong” means house, and such houses are associated with a mythical people called Torro. One man is standing in front of the entrance, while two others are standing on the flat roof.

Jebel Gurgei, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Weeding millets. During “beer-work parties” (Fur: “tawisa”, Arabic: “nafir”), an individual cultivator (man or woman) mobilizes neighbours (men and women) for work by serving them beer (Fur: “kira” Arabic: “merissa”) and sometimes some food. Refusal to accept an “invitation” is taken as an indication of an “unfriendly” relation.

Western foothills of Jebel Marra.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A big beer-work party (Fur: “Bambani”) arranged by a man to honour his mother in law (Fur: “iya mare”, Arabic: “naseeba”) by inviting a large group of people and providing them with ample amounts of beer (Fur: “kira”) and entertainment for those who participate in the work. One man is blowing on a kudu horn while another one is drumming.

Western foothills of Jebel Marra. Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A big beer-work party (Fur: “Bambani”) arranged by a man to honour his mother in law (Fur: “iya mare”, Arabic: “naseeba”) by inviting a large group of people and providing them with ample amounts of beer and entertainment for the participants in the work party.

Western foothills of Jebel Marra.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Two women winnowing millet (Fur: “sona”, Arabic: “dukhn”). Note the terraces for rainy-season cultivation in the background. Terraces in the Jebel Marra region are mainly used as a technique of soil conservation, and they are only to a very small extent used for dry-season irrigated cultivation.

Umu village, Jebel Marra, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A Fur woman grinding sorghum (Fur: “marga”, Arabic: “durra”) on a well-used grinder (Fur: “dida”- lower grinder, “manang” – upper grinder). Millet products are of special symbolic importance in Fur society. Millet flour mixed with water is in Fur language called “bora fatta” (meaning “milk white” – mother’s milk) and is used as a blessing on several ritual occasions (e.g. circumcision, rain rituals, war rituals, treatment of diseases, weddings).

Sarar village, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

Fur women making porridge (Fur “nung”, Arabic “asida”). Millet products like porridge and beer constitute the staple food among the Fur. They are products that belonged to the domestic sphere and should not be transacted in the market. Subjecting them to sale in the market was categorized as shame (Fur: “ora”) like selling sex.

Kebe village, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Men drinking beer (Fur: “kira”) during a break in communal house building. Beer is a product that the wife makes for her husbands from millets taken from his granary. It is shameful to sell millet beer. In daily context, men and women generally consume it separately. Otherwise it is used as a major way of mobilizing neighbours for individual undertakings like house building and weeding.

Umu village, Jebel Marra, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A Fur farmer with his throwing stick (Fur: “dolfa”, Arabic: “sofrog”) and his spears (Fur: “Kor”, Arabic: “harba”) in front of his sweet potato (Fur: “bambai”, Arabic: “bambai”) field.

Note that the acasia albida (Fur: “kurul”, Arabic: “haraz”) trees shed the leaves in the rainy season.

Wadi Azum area, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

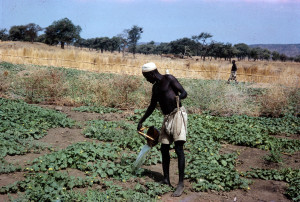

A Fur farmer watering his field of melons (Fur: “burto”). The water is lifted from a shallow well (Fur: “ro”) by a “shadouf” (a water lifting device) and brought in a calabash (Fur: “kere”) to the field (Fur: “rei”).

A Fur farmer watering his field of melons (Fur: “burto”). The water is lifted from a shallow well (Fur: “ro”) by a “shadouf” (a water lifting device) and brought in a calabash (Fur: “kere”) to the field (Fur: “rei”).

Wadi Azum area, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1966

In the western foothills of Jebel Marra small perennial streams allow for a limited amount of dry season irrigated cultivation. A woman harvesting a field of onions (Fur: “basala”, Arabic: “bassal”) that has been irrigated by the water channels in the foreground. In the background rise the western foothills of Jebel Marra.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1966

An elderly woman of the blacksmith/potter caste (Fur: “mir”) has prepared the body (Fur:” kiri”) of three pots in the foreground. She is now crushing fine-grained clay on a grindstone (Fur: “dida”) to be smeared on the interior wall of the pot.

Toumra village, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

A woman of the “mir” caste is adding graphite to the interior wall of one of the pots she is making. Note the broken pot in the background, which contains graphite, and the pot with red ochre coloured water to be smeared on the outside wall of the pot before drying.

Sarar village, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

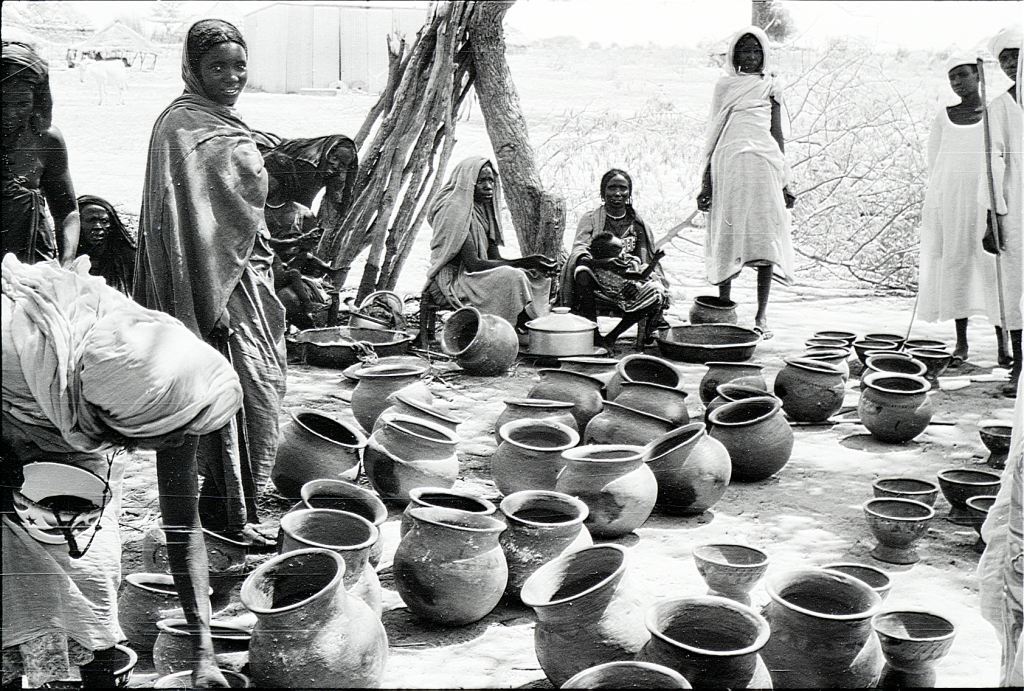

Women of the “mir” caste are selling pots at the local souq (market place). Ceramic goods are associated with the stigmatized “mir” identity and are transacted at a distance from the central market place where agricultural and pastoral products are transacted.

Kutum, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Two men of the blacksmith/potter caste (Fur: “mir”) are preparing the furnace for the iron smelting process. Fur farmers generally use the same word “nonum” for furnace and granary. Both granary and furnace are metaphorically linked to two different aspects of womanhood; one with woman as mother (granary – it is the mother who is responsible for cultivating grain to feed her children), and the other with woman as sex partner (furnace – smelting activities are explicitly associated with sexual intercourse). The blacksmiths, however, use a special word for the furnace, namely “bood”, probably because it is a specialized term among these stigmatized craftsmen. Note the ferricrete sandstone in the foreground.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

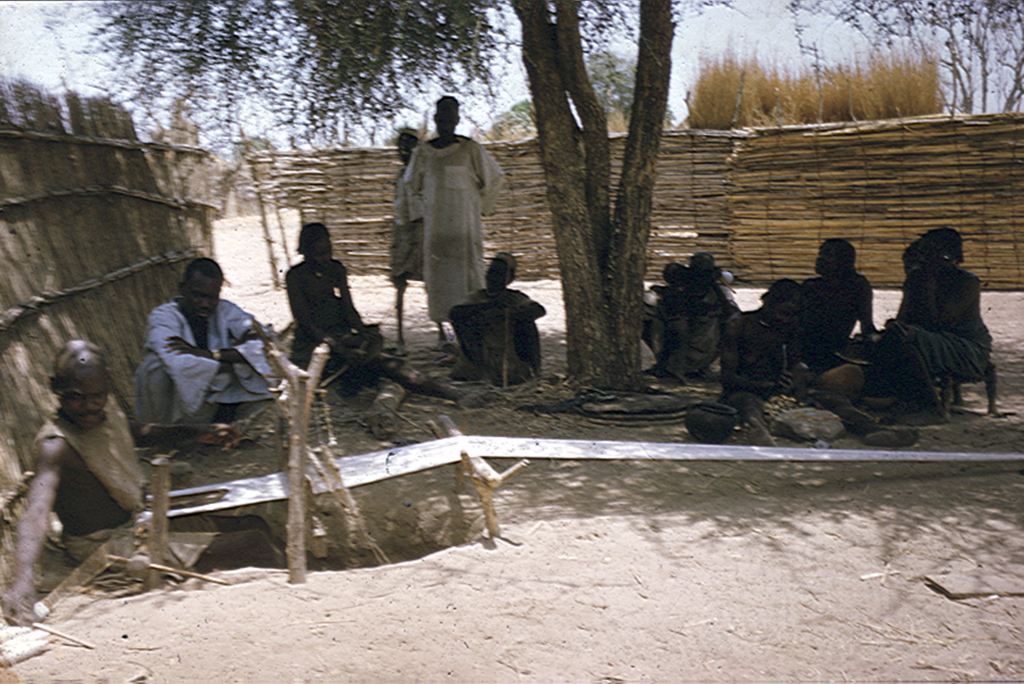

Men of the blacksmith/potter caste (Fur: “mir”) are making tuyeres of clay to be attached to the bellows (Fur: “swi”) used for blowing air into the furnace during smelting of iron (Fur: “daura”). While ordinary pottery making is performed by women of the “mir” caste, the making of clay tuyeres is undertaken by men.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Men of the “mir” caste are making the clay tuyeres (Fur: “borongot”) required for blowing air into the furnace during smelting. The making of tuyeres can easily be associated with sexual intercourse and during the work the “mir” entertain themselves with a rich repertoire of songs with rather explicit sexual metaphors.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Men of the “mir” caste are inserting tuyeres (Fur: “borongot”) at the base of an iron furnace. Note the painted decoration on the body of the furnace.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

The smelting of iron is carried out by men of the “mir” caste who are specialized in that craft (women of the “mir” caste are specialized in pottery making). In this photo a man is making charcoal (Fur: “minina”) to be used in the smelting process.

Toumra village, Northern Darfur.

Two blacksmiths of the “mir” caste forging an axe (Fur: “bou”, Arabic: “fas”) at the local souq (market place). Iron goods are associated with the stigmatized “mir” identity and are transacted at a distance from the central market place where agricultural and pastoral products are transacted.

Kutum, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

A beer-work party is organized in connection with house building. The workers are constructing the wooden frame of the conical roof that will be covered by thatch. What is emphasized in the beer-work party is solidarity among equal neighbours, instead of the hierarchy implied by paid work.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Drummers entertaining participants in a house-building party (Fur: “tawisa”). The festive character of communal works like house-building and agricultural tasks is further emphasized by lavish provision of beer (Fur: “kira”) and food. Provision of beer is not seen by the Fur as payment for work but as part of egalitarian relations between neighbours.

Village in Wadi Saleh area, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A Fur woman is drumming next to the underground nests of flying ants (Fur: “simoa”). The sound produced by drumming is apparently a signal similar to rain-drops and entices the ants to come out of their nest. Fried flying ants are a favored delicacy in Jebel Marra villages.

Umu village, Jebel Marra.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Traditional sesame oil mill (Arabic: “assara”) carved out of a tree trunk. Note how the pounder in the middle of the mill is connected to the lever loaded with stones in the foreground. When the camel moves around the mill, this increases the force the pounder exerts on the sesame seeds and thereby increases the amount of oil extracted. The extracted oil is sold in the market (souq).

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A man at his loom (Fur: “shaaka”). Spinning and weaving of cotton are considered male work. At marriage, a man should present his mother in law (Fur: “iya mare”, Arabic: “naseeba”) with a woven garment.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Circumcision of boys is an important ceremony in Fur communities and lasts for several days. It involves consumption of local beer (Fur: “kira”) and prestigious food like meat (Fur: “nino”), and involves festive activities with dancing, most importantly the ritualized “dance of the gazelle”, (Fur: “ferangabie”). The songs sung by the women contain very explicit references to sexual intercourse and the female genitalia (Fur: “sendi”).

Amballa, Lower Wadi Azum, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Celebrations in connection with circumcision of boys (Fur: “dogola kandi”, Arabic: “tahura”). Note the cowrie shells (Fur: “kandura”, Arabic: “wadda”) used as ornament in the hair of the lady to the left of the man in the middle. Cowrie have been reported to be used as a medium of exchange until 150 years ago and connected Darfur in a widespread exchange network from the Red Sea to the Atlantic Ocean. All the time cowries have served as female ornaments and frequently used on ceremonial occasions. A cowrie shell has a form that often trigger metaphoric associations with the female genitalia.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Communal festivities at circumcisions are very important among the Fur. In this photo, women are dancing “the gazelle dance” ( Fur: “ferangabie”) around the hut where the circumcision (Fur: “dogola kandi”, Arabic: “tahura”) will be performed.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Drumming, singing, and dancing are important events connected with circumcision (Fur: “dogola kandi”, Arabic: “tahura”). Note the man dressed as a woman to the left of the drummers. He is a male relative of a boy to be circumcised. Also note the women with sticks and sometimes weapons ordinarily carried by men. A characteristic feature of circumcision rituals is that many participants are using cultural elements associated with the opposite gender.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Circumcision festivities with procession of women carrying objects related to food making as well as others related to male activities like hunting and warfare. This procession is called “ferangabia” which in Fur language means “the dance of the gazelle”. Note the cowrie shells (Fur: “kandura”, Arabic: “wadda”) in women’s hair: the shape of cowrie lends itself to metaphoric association with the vagina (Fur: “sendi”).

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A variety of cultural elements (associated with males as well as females) are improvised in the festive activities taking place at circumcision. On this photo a decorated camel (Fur: “kamal”) on which the boy to be circumcised rides from the place where he has been secluded during the liminal period (neither child, nor adult) to the place of circumcision that signify transition to manhood. Note the amber (Fur: “zumam”, Arabic: “zeitun” – meaning in fact olives) beads attached to the helmet. This combination of female and male associated elements emphasizes the liminal position of the boy to be circumcised.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Fur women are fetching water from a shallow pond by means of calabashes (Fur: “kere”) and pouring it into clay pots (Fur: “tawu”) that they carry on their heads back to the village. Activities connected with food preparation like grinding grains, collecting firewood, fetching water (Fur: “koro”) are considered female work.

Lower Wadi Azum, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A Fur woman making stone grinders (Fur: “munang”- upper grinder, “dida” – lower grinder). A syndrome of activities associated with food preparations, like fetching water and firewood, making pots, and even, as this picture shows, making grinders of stone are considered female activities.

A hill site near Dor, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

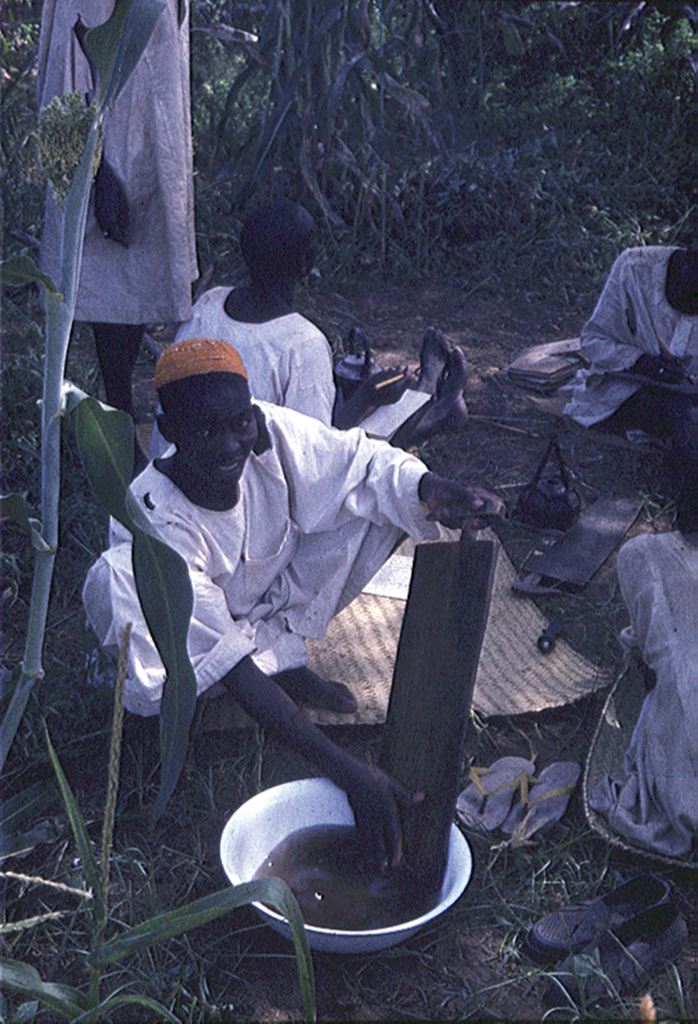

Fur boys who do not go to government schools will for periods of 4 to 6 years attend Koran schools (Fur: “som”) where they are instructed by local faqihs (Arabic for “holy men”) teaching them to write verses from the Koran. During this period they generally attend schools led by different faqihs, involving movements over areas covering large parts of Darfur. These Koran school boys (Arabic and Fur: “Muhagerin”) are on the way to a new faqih in a different village. During the studies they subsist on alms given by the people of the villages where they study. Note the wooden board (Arabic and Fur: “loh”) that the boy to the left is carrying on his shoulder. It is on this board they are trained to write Koranic verses by locally produced ink (Fur: “dawai”, Arabic: “hibr”).

Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A group of Fur villagers are writing down Koran verses on the traditional writing boards (Arabic and Fur: “loh”) in connection with preparing healing water for a sick person. The ink written verses are washed off from the board and the water is believed to have a healing effect.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Two Fur men are writing on their wooden boards (Arabic and Fur: “loh”) holy verses from the Koran. When they have filled the board with writings the ink (Fur: “dawai”, Arabic: “hibr”) is washed off and poured into the pots. The holy water is believed to a have a curing effect on sick people.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A Fur man is washing ink used to write Koranic verses off his writing board (Arabic and Fur: “loh”). The magic significance of the written Islamic text is exemplified in the belief that drinking this water has a healing effect.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A young Fur woman in an isolated village on Jebel Gurgei is leaving the family compound. Note that she is not dressed according to the Islamic codes, although she is a Muslim.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A Fur woman is standing with her baby on the alluvial soils of wadi Aribo. Note the acacia albida trees (Fur: “kurul”, Arabic: “haraz”) in the background. The acacia albida trees are a characteristic feature of the lower wadis of Western Darfur. During the dry season the pods of the acacia albida provide nutritious food for the cattle of the Baggara Arab nomads who in this season camp on the harvested fields under the trees. The dung from the cattle serves to fertilize the fields of the Fur farmers who cultivate them in the rainy season. In the rainy season the acacia albida trees shed their leaves. This photo is from the dry season.

Wadi Aribo, near Zalingi, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1966

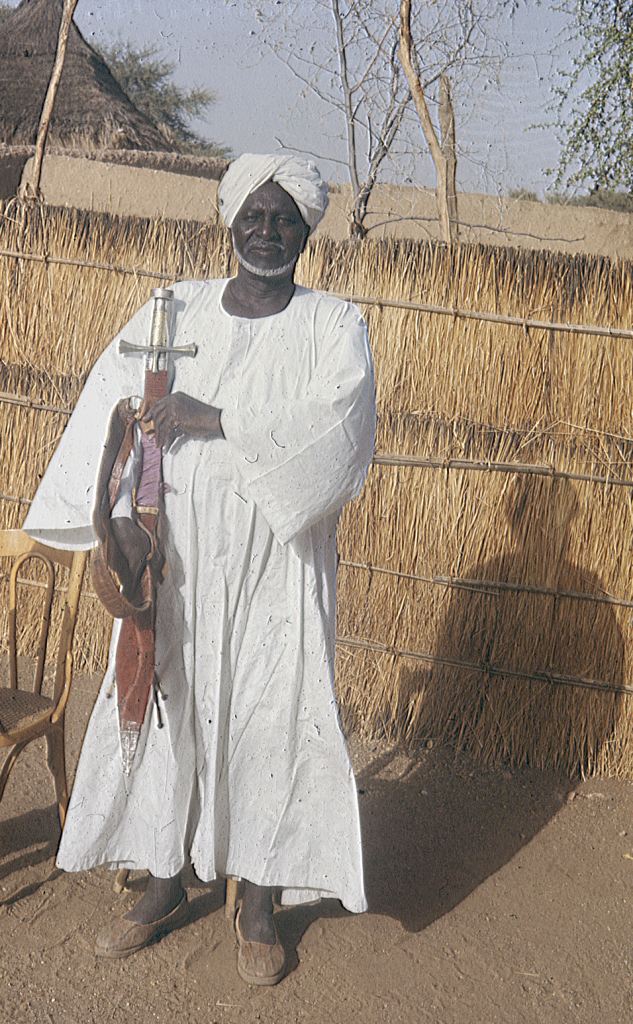

One of the sons of the last sultan of Darfur, Ali Dinar (killed in 1916 west of Zalingi while fleeing from the British invasion force).

El Fashir, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A group of nomadized Fur watering a donkey (Fur: “lel”) at their camp in the area of Jebel Si. Note the seasonal huts made of branches in the background. They are very different from the tents used by nomadized Fur in western Darfur. In the Jebel Si area nomadized Fur farmers do not change ethnic identity.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

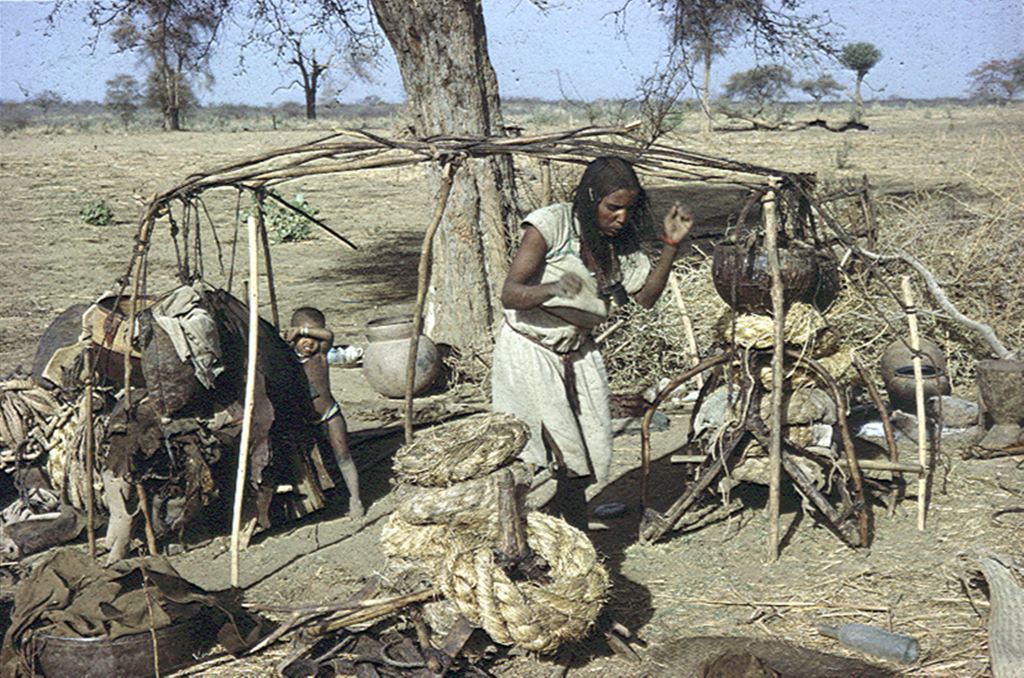

The camp site of a Fur farmer who has succeeded in accumulating cash for investment in a sufficient number of cattle. Cattle thrive best when they are moved seasonally between different ecological zones. Successful Fur farmers therefore prefer to establish themselves as nomads like the Baggara Arabs when they have enough cows (Fur: “ko”). Note the tent made of straw mats (Fur and Arabic: “birish”) similar to those used by the Baggara nomads.

Lower Wadi Azum, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A Baggara family outside their tent.

Western foothills of Jebel Marra, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A Baggara Arab man and child riding an ox on their migration from the dry season grazing area in western Darfur to their own rainy season “dar” (homeland in Arabic) in Id el Ghannam, southern Darfur. Note the lance (Arabic: “shalaqaya”) he is carrying.

Amballa, Lower Wadi Azum.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Although the Baggara Arabs are associated with migratory cattle husbandry, it is only the richest who have cattle herds large enough to yield a cash income required to satisfy their consumption needs for grain and other goods. Most Baggaras therefore practice some cultivation in their home area (dar) during the rainy season. This Baggara man is sowing sorghum with the traditional seluka mode (making holes in the ground with the stick to plant the seeds therein).

Gidad, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1973

A woman from the Jumala Arabs of Northern Darfur is setting up the tent in a dry season camp (Arabic: “fariq”), near Wadi Aribo, close to Zalingi.

Wadi Aribo, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1966

A group of Jumala Arab nomads from Northern Darfur migrating through the Fur area of Western Darfur, after the Fur have harvested their fields. In the 1960s and 1970s relations between the Fur and Arab groups, like the Baggara and Jumala, were quite peaceful. From the 1980s tensions were growing, and from the turn of the millenium the Baggarta and Jumala Arabs have been very active in the Janjaweed militias fighting the Fur farmers.

Zalingi area, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1966

At a camp of the Woodabe Fulani nomads during their migration into Fur area towards the end of the rainy season. The Fulani are found in the Sahel/Savannah zone from Senegal to the border of Ethiopia. As cattle herders they compete with the Baggara Arabs for pasture and water.

Southern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1973

Fulani herders of the Woodabe tribe lead a herd of longhorn cattle (called “kuri” in Sudan, not to be confused with the “kuri” cattle race of Lake Chad) on the migrations from Central African Republic into dry season pastures in Darfur. The Fulani have a remarkable control over their livestock and can lead them with verbal commands. Note the Fulani clothing that differs from that used by Baggara nomads. The Fulani are in Sudan frequently referred to as “Fellata”, a term that is applied to people coming from West Africa in general. In Darfur, the term “Fellata” is also used for one of the Baggara Arab tribes who have their own district and administration with headquarter in Tullus. Within the Fellata tribe there is a subunit (“omodiya” in Arabic) at Gereida that the Fullani nomads are attached to. To distinguish the Fullani herders from the Fellata Baggara they are usually referred to as Umbororo Fellata.

Tullus district, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1973

A couple of the Weila Fulani is setting up their tent towards the end of the rainy season. The Fulani nomads generally move into the Fur area before the Baggara Arabs and they are also the first to move southwards as the rain approaches.

Near Nyertete, Western foothills of Jebel Marra, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A Fulani nomad of the Weila tribe is demonstrating his skills as an archer. The typical Fulani weapons are the bow and arrow, in contrast to the lance (Arabic: “shalaqaiya”) that is the typical weapon of the Baggara nomads.

Near Nyertete in the western foothills of Jebel Marra, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A group of Kinin, a branch of the Tuaregs of the Sahel/sahara zone of North West Africa. They constitute a minority tribal group in Darfur, subsisting by both farming and herding. Like Tuaregs of Algeria some of the Kinin men on this picture cover their face with a veil.

Tawila village between El Fashir and Kebkabiya, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Selling agricultural crops provides cash income for local Fur farmers. Most selling takes place at the weekly souq (Arabic for “market”), but sometimes in the home of a cultivator. In this photo, a Fur is selling millet (Fur: “sona”) to an Arab trader.

In a village of the western foothills of Jebel Marra, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

The weekly market (Arabic: “souq”) is important in the Fur village economy. In this photo, a Fur woman is selling dried tomatoes (Fur: “futta”) and dried ochre (Fur: “faga kirro” – literally meaning “black ochre”) to an Arab trader at the souq of Amballa.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Beer plays a very important role in the life of the Fur, not only nutritionally but also symbolically. It is a major item in rituals that serve to indoctrinate ideas of solidarity among community members. To sell beer is considered an act similar to selling sex. Women who sell beer are thus considered like prostitutes (Fur: “azaba”). In this photo, Fur women from the village of Umu in Jebel Marra are engaging in such an “immoral” act (Fur: “ora”). Shameful sales used to take place at a distance from the central market space.

Umu village, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965