A man and his daughter stand outside a flat-roofed Torrontonga house (Fur: “Tong)”. Note that in those days the Muslim Fur of Jebel Si did not practice a strict Islamic dress code for females.

Jebel Si area.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Circumcision of boys is an important ceremony in Fur communities and lasts for several days. It involves consumption of local beer (Fur: “kira”) and prestigious food like meat (Fur: “nino”), and involves festive activities with dancing, most importantly the ritualized “dance of the gazelle”, (Fur: “ferangabie”). The songs sung by the women contain very explicit references to sexual intercourse and the female genitalia (Fur: “sendi”).

Amballa, Lower Wadi Azum, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Celebrations in connection with circumcision of boys (Fur: “dogola kandi”, Arabic: “tahura”). Note the cowrie shells (Fur: “kandura”, Arabic: “wadda”) used as ornament in the hair of the lady to the left of the man in the middle. Cowrie have been reported to be used as a medium of exchange until 150 years ago and connected Darfur in a widespread exchange network from the Red Sea to the Atlantic Ocean. All the time cowries have served as female ornaments and frequently used on ceremonial occasions. A cowrie shell has a form that often trigger metaphoric associations with the female genitalia.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Communal festivities at circumcisions are very important among the Fur. In this photo, women are dancing “the gazelle dance” ( Fur: “ferangabie”) around the hut where the circumcision (Fur: “dogola kandi”, Arabic: “tahura”) will be performed.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Drumming, singing, and dancing are important events connected with circumcision (Fur: “dogola kandi”, Arabic: “tahura”). Note the man dressed as a woman to the left of the drummers. He is a male relative of a boy to be circumcised. Also note the women with sticks and sometimes weapons ordinarily carried by men. A characteristic feature of circumcision rituals is that many participants are using cultural elements associated with the opposite gender.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Circumcision festivities with procession of women carrying objects related to food making as well as others related to male activities like hunting and warfare. This procession is called “ferangabia” which in Fur language means “the dance of the gazelle”. Note the cowrie shells (Fur: “kandura”, Arabic: “wadda”) in women’s hair: the shape of cowrie lends itself to metaphoric association with the vagina (Fur: “sendi”).

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A variety of cultural elements (associated with males as well as females) are improvised in the festive activities taking place at circumcision. On this photo a decorated camel (Fur: “kamal”) on which the boy to be circumcised rides from the place where he has been secluded during the liminal period (neither child, nor adult) to the place of circumcision that signify transition to manhood. Note the amber (Fur: “zumam”, Arabic: “zeitun” – meaning in fact olives) beads attached to the helmet. This combination of female and male associated elements emphasizes the liminal position of the boy to be circumcised.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

Fur boys who do not go to government schools will for periods of 4 to 6 years attend Koran schools (Fur: “som”) where they are instructed by local faqihs (Arabic for “holy men”) teaching them to write verses from the Koran. During this period they generally attend schools led by different faqihs, involving movements over areas covering large parts of Darfur. These Koran school boys (Arabic and Fur: “Muhagerin”) are on the way to a new faqih in a different village. During the studies they subsist on alms given by the people of the villages where they study. Note the wooden board (Arabic and Fur: “loh”) that the boy to the left is carrying on his shoulder. It is on this board they are trained to write Koranic verses by locally produced ink (Fur: “dawai”, Arabic: “hibr”).

Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969

A group of Fur villagers are writing down Koran verses on the traditional writing boards (Arabic and Fur: “loh”) in connection with preparing healing water for a sick person. The ink written verses are washed off from the board and the water is believed to have a healing effect.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

Two Fur men are writing on their wooden boards (Arabic and Fur: “loh”) holy verses from the Koran. When they have filled the board with writings the ink (Fur: “dawai”, Arabic: “hibr”) is washed off and poured into the pots. The holy water is believed to a have a curing effect on sick people.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

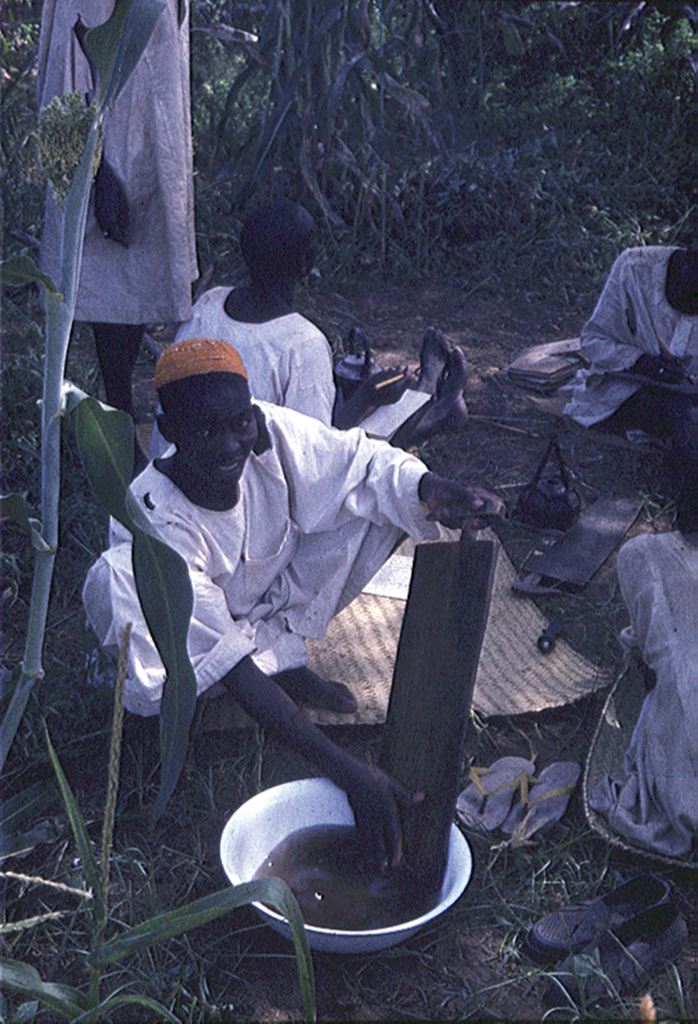

A Fur man is washing ink used to write Koranic verses off his writing board (Arabic and Fur: “loh”). The magic significance of the written Islamic text is exemplified in the belief that drinking this water has a healing effect.

Amballa, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965

A young Fur woman in an isolated village on Jebel Gurgei is leaving the family compound. Note that she is not dressed according to the Islamic codes, although she is a Muslim.

Jebel Si area, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1969