A woman mixing clay (Fur: “daalu” ) with sorghum residue as temper for the pots (Fur: “tewe”) she is making.

Sarar village, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

An elderly woman of the blacksmith/potter caste (Fur: “mir”) has prepared the body (Fur:” kiri”) of three pots in the foreground. She is now crushing fine-grained clay on a grindstone (Fur: “dida”) to be smeared on the interior wall of the pot.

Toumra village, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

A woman of the “mir” caste is adding graphite to the interior wall of one of the pots she is making. Note the broken pot in the background, which contains graphite, and the pot with red ochre coloured water to be smeared on the outside wall of the pot before drying.

Sarar village, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

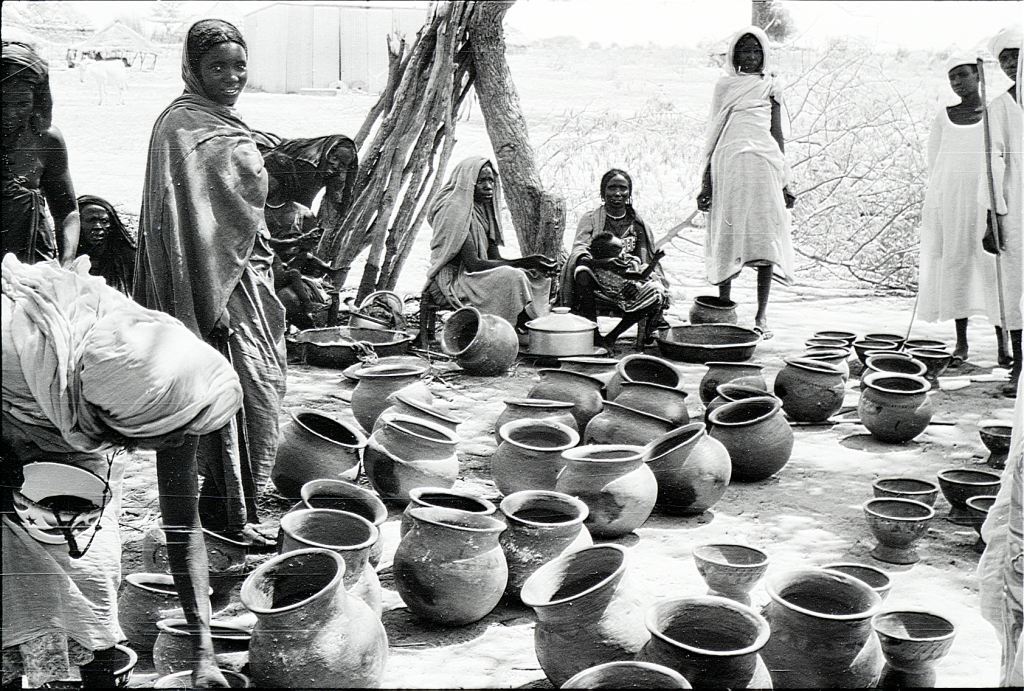

Women of the “mir” caste are selling pots at the local souq (market place). Ceramic goods are associated with the stigmatized “mir” identity and are transacted at a distance from the central market place where agricultural and pastoral products are transacted.

Kutum, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Two men of the blacksmith/potter caste (Fur: “mir”) are preparing the furnace for the iron smelting process. Fur farmers generally use the same word “nonum” for furnace and granary. Both granary and furnace are metaphorically linked to two different aspects of womanhood; one with woman as mother (granary – it is the mother who is responsible for cultivating grain to feed her children), and the other with woman as sex partner (furnace – smelting activities are explicitly associated with sexual intercourse). The blacksmiths, however, use a special word for the furnace, namely “bood”, probably because it is a specialized term among these stigmatized craftsmen. Note the ferricrete sandstone in the foreground.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Men of the blacksmith/potter caste (Fur: “mir”) are making tuyeres of clay to be attached to the bellows (Fur: “swi”) used for blowing air into the furnace during smelting of iron (Fur: “daura”). While ordinary pottery making is performed by women of the “mir” caste, the making of clay tuyeres is undertaken by men.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Men of the “mir” caste are making the clay tuyeres (Fur: “borongot”) required for blowing air into the furnace during smelting. The making of tuyeres can easily be associated with sexual intercourse and during the work the “mir” entertain themselves with a rich repertoire of songs with rather explicit sexual metaphors.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Men of the “mir” caste are inserting tuyeres (Fur: “borongot”) at the base of an iron furnace. Note the painted decoration on the body of the furnace.

Toumra, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

The smelting of iron is carried out by men of the “mir” caste who are specialized in that craft (women of the “mir” caste are specialized in pottery making). In this photo a man is making charcoal (Fur: “minina”) to be used in the smelting process.

Toumra village, Northern Darfur.

Two blacksmiths of the “mir” caste forging an axe (Fur: “bou”, Arabic: “fas”) at the local souq (market place). Iron goods are associated with the stigmatized “mir” identity and are transacted at a distance from the central market place where agricultural and pastoral products are transacted.

Kutum, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978