A woman mixing clay (Fur: “daalu” ) with sorghum residue as temper for the pots (Fur: “tewe”) she is making.

Sarar village, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

An elderly woman of the blacksmith/potter caste (Fur: “mir”) has prepared the body (Fur:” kiri”) of three pots in the foreground. She is now crushing fine-grained clay on a grindstone (Fur: “dida”) to be smeared on the interior wall of the pot.

Toumra village, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

A woman of the “mir” caste is adding graphite to the interior wall of one of the pots she is making. Note the broken pot in the background, which contains graphite, and the pot with red ochre coloured water to be smeared on the outside wall of the pot before drying.

Sarar village, Southern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1973

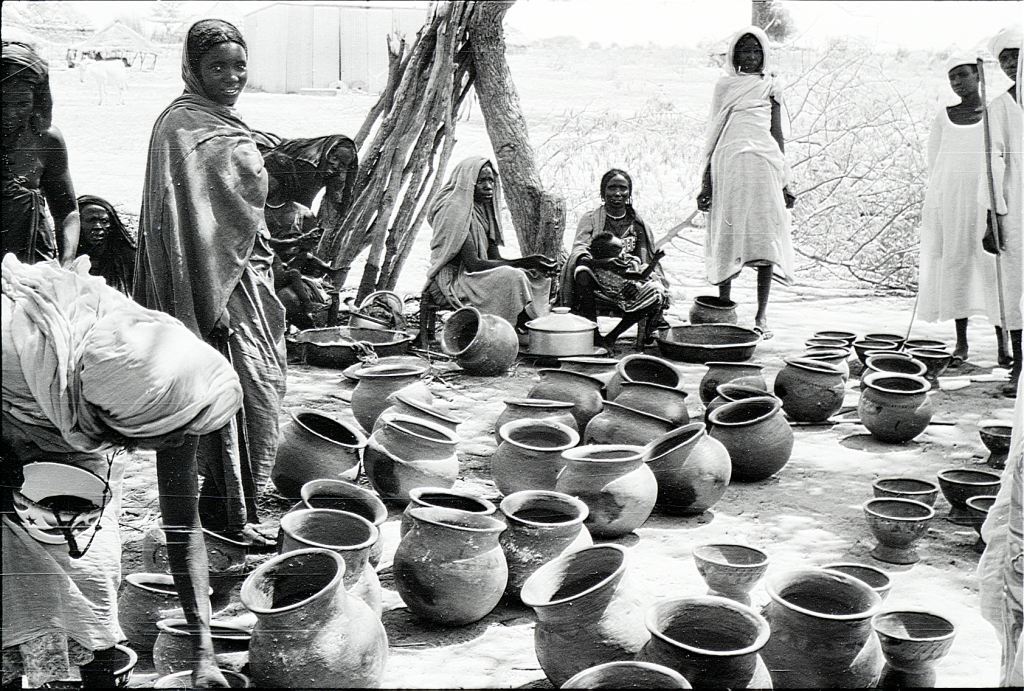

Women of the “mir” caste are selling pots at the local souq (market place). Ceramic goods are associated with the stigmatized “mir” identity and are transacted at a distance from the central market place where agricultural and pastoral products are transacted.

Kutum, Northern Darfur.

Photo: Randi Haaland, 1978

Fur women are fetching water from a shallow pond by means of calabashes (Fur: “kere”) and pouring it into clay pots (Fur: “tawu”) that they carry on their heads back to the village. Activities connected with food preparation like grinding grains, collecting firewood, fetching water (Fur: “koro”) are considered female work.

Lower Wadi Azum, Western Darfur.

Photo: Gunnar Haaland, 1965